The Psychiatric Hospital Part 3 - Seclusion

/While I thought I’d never go into one, I’m certainly glad it was available when I needed it.

Read MoreWhile I thought I’d never go into one, I’m certainly glad it was available when I needed it.

Read MoreMy seclusion room story requires a bit of set up.

I voluntarily committed myself to Ridgeview in 2011, and was given a brief tour to get comfortable with my new little world. Part of that world was a seclusion room.

It’s pretty bare, but safe.

It consisted of four walls with a solid, rubber mattress on the floor. Why solid rubber? So that someone could not strangle themselves with sewn fibers.

A brilliant white light radiated from the light fixture that was mounted flush with the ceiling. Why flush? So that someone could not hang themselves from it.

A substantial, but easily opened door with a large window separated this little psych ward from the big psych ward. Why the window? So the nurses could keep an eye on the patient. The door was strategically located directly across from the nurse’s station for even easier tracking.

There is no straight jacket, no one is getting chained to the wall, and no one is locked in without round-the-clock supervision. But, I distinctly remember thinking,

“I’ll never be in one of those.”

Life, as I have come to learn, loves irony.

In the fall of 2016, I had the “choice” between involuntary commitment or voluntary commitment at a facility in Maryland. More on that in a later post.

After my release, I entered an Intensive Outpatient Program, or IOP. Basically, you go to the hospital every morning, stay till three, and get to sleep in your own bed at night. This program gradually gets a person into a more regular routine, and they can more easily transition into the life they choose to live.

Bedlam from 'A Rake's Progress' 1733, By William Hogarth - “Bedlam” was the byname of Bethlem Royal Hospital due to the noise. Visitors were welcome! For a shilling or two, you could walk through the hospital and gawk at the crazy people.

I was there for extreme panic attacks, that were a side effect of a new medication I was cycled onto by my psychiatrist. I have never experienced such terror, and I hope to never experience anything close to the sensations I had while on that medication. I write this because it explains why I needed the seclusion room on a crisp Friday afternoon in November.

“They’re looking at me.”

“They’re spying on me.”

“They’re judging me.”

Such are the thoughts of a paranoid mind in the early stages of a panic attack. Truth be told, the nursing students had no idea who I was, and they certainly had no evil intentions toward me. But, my mind was unaccustomed to seeing them. The unexpected and unwanted presence of several new faces in my safe hospital ward triggered a massive panic attack.

Almost entirely paralyzed by fear, I somehow got a nurse’s attention and communicated with him by grunting and shaking my head “yes” or “no” to his questions. He gave me a high strength, anti-anxiety medication, which was nice, but at that point, it was about as effective as putting a single sandbag in the path of a massive flood. Using our meager method of communication, we agreed that I wanted to go into the seclusion room to feel safe and ride out the worst of the panic attack, but I could not move.

Four nurses picked me up in my chair and placed me in the room. They lifted me out of the chair, removed my clothes and put a paper gown on me. Why paper? Think about it and you’ll realize why.

A nurse asked if she would be safe sitting in the room with me. I grunted, “yes,” but my mind was on fire, and after a few minutes I told her:

“I need you to get out of this room and lock the door.”

She did, and I lost it.

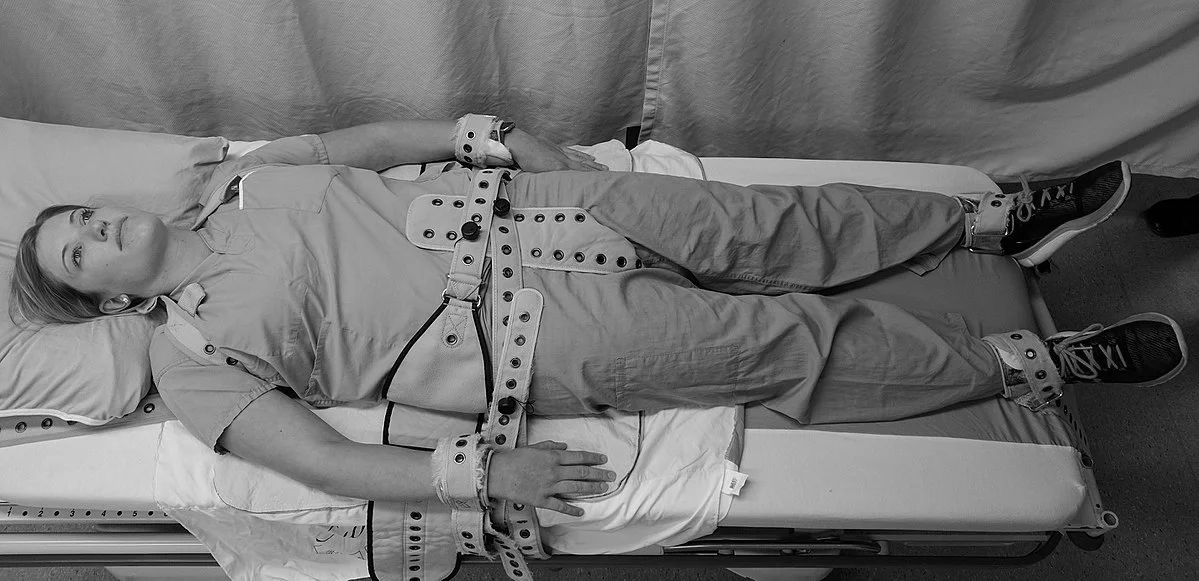

Dramatic recreation

You already know that seclusion rooms are designed to prevent someone from significantly hurting themselves. I knew this too. So I used the room to cause pain that I could control.

I punched the walls. I chained combinations together until my knuckles bled. I screamed. I paced. I raged. When I could no longer lift my hands, I slammed my head against the wall.

I did not feel agony. I WAS agony.

I unleashed all of my panicked energy while the nurses and doctors pleaded for me to stop. Protocol dictated that they stay outside the room. Sure, it would have been nice to have someone restrain me, but the safer course is to let a person burn themselves out until they are no longer a threat to themselves or their caretakers.

Most hospital protocols specify that restraints be used for the least amount of time necessary.

Eventually, everything slowed down. I collapsed onto the mattress and the door opened up. Several large men secured my limbs and put me on a gurney, to which my wrists and ankles were strapped.

Didn’t I write no restraints earlier? They are used as a final resort to protect a person who has clearly demonstrated the recent capacity to hurt themselves, and to protect those around them.

A nurse injected me with Haldol, an antipsychotic drug that “decreases excitement of the brain.” It’s the human equivalent of horse tranquilizer - you get real chill, real quick. Then she gave me another injection to counteract the side effects of Haldol.

I woke up two days later with a pounding headache and swollen knuckles, and all I could think of was how wrong I was so many years ago.

Life on the 7th Shelf is my way of sharing how a person can live well with depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation.

The 7th Shelf was written by Dante in The Inferno, as the Wood of the Suicides.

For me, living on the 7th shelf is challenging but I have found my means for winning the daily battle against the worst my mind can throw at me.

We aim to create a space of hope, filled with resources, information, tools, and more for mental health awareness and suicide prevention. We’re committed to Gordon’s vision of sharing different methods of thinking to help those with and without mental illness live more fulfilling lives.

Contact us

corsetti007@me.com

Call or text 988 for the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline for help. In an emergency, please call 911.

If you or someone you know is seeking help for mental health concerns, visit the National Alliance on Mental Health (NAMI) website, or call 1-800-950-NAMI(6264).

For confidential treatment referrals, visit the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) website, or call the National Helpline at 1-800-662-HELP(4357).