Revisiting Electroconvulsive Therapy - Part 4

/I hope that this post encourages those that are suffering, and those caring for loved ones, to research these different treatments.

Read MoreI hope that this post encourages those that are suffering, and those caring for loved ones, to research these different treatments.

Read MoreI was willing to sacrifice my long-term health for short-term freedom.

Read MoreWhile I thought I’d never go into one, I’m certainly glad it was available when I needed it.

Read MoreEven the clothes I wore were searched for contraband or tools I could use to harm myself.

Read MoreI hope that this post encourages those that are suffering, and those caring for loved ones, to research these different treatments.

Read MoreThe objective of this post, and a few future posts in this series, is to shed light on what is a scary proposition for most people and their families.

Read MoreIt took my fourth hospitalization before I realized the folly of lying to expedite my release.

During my first three hospitalizations, I learned the rules and then acted accordingly. Doctors, nurses, and other caretakers are, in my experience, personally invested in a person getting well. I had many wonderful interactions with compassionate and empathetic professionals at each hospital where I spent time. That said, the medical business is a business.

Insurance companies are not keen on paying for beds for patients who are stable. A hospital cannot be financially sound if patients are kept on the ward until their caretakers are absolutely sure a patient is capable of taking care of themselves, or at the very least, not in any danger of self-harm.

It is a system that constantly cycles people in and out. Because it is a system, though, it can be gamed.

I am exceptionally good at putting on a facade to the world. In my first hospitalizations, I lied.

Told the nurses I felt great. I smiled. I held doors open for other patients. I politely requested shaving privileges, and did my very best to be of no concern to those running the ward. This strategy worked brilliantly to get me released because there was no behavior the doctors or nurses could point to where I demonstrated the desire for self-harm.

I appeared psychologically “stable,” and that meant I should be released, and my bed given to someone at more acute risk of overdose, self-harm, etc.

I knew the system. I had read about emergency psychiatric hospitals and insane asylums. The best patient is typically one that causes no problems. So I lied and became the best patient I could at the expense of my health.

At this point someone might rightly condemn me: “How could you lie to your doctor? Didn’t you want to get better?” Spare me.

If everyone told their doctor the truth, there would be no medical drama category on Netflix.

I wanted out of the hospital, and I was willing to sacrifice my long-term health for short-term freedom.

There are no quick fixes for mental illness, and lying can only be maintained for so long. Eventually, I did not have the energy to keep the facade going. My mask of normality crumbled away.

My last hospitalization was a result being committed following my outburst in the seclusion room. I stayed in my bed for days. A nurse kept coming into my room to encourage me to venture out and interact, but I stubbornly stayed under my sheet. After a while, though, it was pretty boring by myself, and I shuffled outside.

Six years after my first hospitalization I had finally had it with putting on a show of normality. It was exhausting and counter-productive. Once I stopped playacting and started working on my recovery, life got better.

It is realistic to expect that I will be back in a psychiatric hospital someday in the future. I learned that fact from a delightful older woman who checked herself into the hospital every year or so for a couple of weeks. She knew that when she did not feel safe, she should be in the safest place possible.

That was a great lesson to learn. I can use the hospital just like any other treatment. That understanding makes it much more bearable to willingly be locked into a ward, watch Law & Order SVU reruns, eat poor food, and talk with doctors.

Using the system, as opposed to gaming the system, was the lesson I wish I knew years and years ago.

Group is a regular part of every day in a psych ward. The type of groups may differ between facilities, but they are invaluable to the patients and to the caretakers.

Facilities have different rules on expected behavior. Ridgeview required me to attend all groups in order to get the privilege of dining in the mess hall. Those that avoided group, got their food delivered to the ward in a styrofoam box. At St. Joseph, food was delivered to the unit so there was no real penalty if you did not attend group, but, since group is a primary method for determining a person’s readiness to leave, attendance is a good idea if you want to get past the locked door at the front of the building.

Most of us went to group begrudgingly. If nothing else, it passed the time. Also, the staff turned off the television during group time.

Looking back, I would say that Ridgeview’s groups were focused on everyday life skills, and St. Joseph’s groups were focused on communication and interpersonal skills.

Behold! My awesome hot plate!

I definitely enjoyed group more at St. Josephs, because they were more fun.

Reminiscent of a kindergarten class. Feel like coloring? Go color! Want to play with blocks? We have all the blocks! I even learned to grout and made my own hot plate over a three day period.

At this point, some readers may be wondering, “Really? Coloring books? This is supposed to make you better?” No. Group does not make a person better. It facilitates recovery because human beings are social creatures.

Isolation can destroy a person. Ask any prisoner who has spent time in solitary. Or, just watch this video about Harry Harlow’s Pit of Despair experiments with rhesus monkeys:

Now, I am an introvert’s introvert. I find nothing more enjoyable than reading a book on a lazy Sunday afternoon, and never saying a word to anyone for the entire day. That said, I am human, and I do not do well with extended periods of isolation. No one does.

Group, in the context of psychiatric care, establishes a place where someone with a frayed mind can get their bearings under controlled circumstances. The depressed person who cannot speak can, at least, listen.

The person coming down from a manic episode can ease out of it with people who won’t judge. The addict who just got through the worsts of withdrawal can talk about their experiences.

The hospital is not real life, and group allows for an approximation of life. As such, it gives insight into a person’s state of mind around other people that is objectively measurable by those providing care.

For instance, for the two days that I avoided group entirely and stayed in my bed, I was not ready to leave the hospital. Because I likely would have gone home, got into bed, and avoided my life. But, oh how a nurse’s face lights up when you walk out of your room and sit down in group! Even if you do not say anything, your presence shows a willingness to engage with others.

Group is a means to an end. It gives patients the opportunity to experience time with people in a controlled setting. Combined with daily therapy, consistent medication, a good diet, and sleep, the whole treatment becomes greater than the sum of it’s parts. It is a staggeringly simple idea, but that is why it works. Put a human being in varied, yet safe, social situations and give them time to learn how to exist with others.

My seclusion room story requires a bit of set up.

I voluntarily committed myself to Ridgeview in 2011, and was given a brief tour to get comfortable with my new little world. Part of that world was a seclusion room.

It’s pretty bare, but safe.

It consisted of four walls with a solid, rubber mattress on the floor. Why solid rubber? So that someone could not strangle themselves with sewn fibers.

A brilliant white light radiated from the light fixture that was mounted flush with the ceiling. Why flush? So that someone could not hang themselves from it.

A substantial, but easily opened door with a large window separated this little psych ward from the big psych ward. Why the window? So the nurses could keep an eye on the patient. The door was strategically located directly across from the nurse’s station for even easier tracking.

There is no straight jacket, no one is getting chained to the wall, and no one is locked in without round-the-clock supervision. But, I distinctly remember thinking,

“I’ll never be in one of those.”

Life, as I have come to learn, loves irony.

In the fall of 2016, I had the “choice” between involuntary commitment or voluntary commitment at a facility in Maryland. More on that in a later post.

After my release, I entered an Intensive Outpatient Program, or IOP. Basically, you go to the hospital every morning, stay till three, and get to sleep in your own bed at night. This program gradually gets a person into a more regular routine, and they can more easily transition into the life they choose to live.

Bedlam from 'A Rake's Progress' 1733, By William Hogarth - “Bedlam” was the byname of Bethlem Royal Hospital due to the noise. Visitors were welcome! For a shilling or two, you could walk through the hospital and gawk at the crazy people.

I was there for extreme panic attacks, that were a side effect of a new medication I was cycled onto by my psychiatrist. I have never experienced such terror, and I hope to never experience anything close to the sensations I had while on that medication. I write this because it explains why I needed the seclusion room on a crisp Friday afternoon in November.

“They’re looking at me.”

“They’re spying on me.”

“They’re judging me.”

Such are the thoughts of a paranoid mind in the early stages of a panic attack. Truth be told, the nursing students had no idea who I was, and they certainly had no evil intentions toward me. But, my mind was unaccustomed to seeing them. The unexpected and unwanted presence of several new faces in my safe hospital ward triggered a massive panic attack.

Almost entirely paralyzed by fear, I somehow got a nurse’s attention and communicated with him by grunting and shaking my head “yes” or “no” to his questions. He gave me a high strength, anti-anxiety medication, which was nice, but at that point, it was about as effective as putting a single sandbag in the path of a massive flood. Using our meager method of communication, we agreed that I wanted to go into the seclusion room to feel safe and ride out the worst of the panic attack, but I could not move.

Four nurses picked me up in my chair and placed me in the room. They lifted me out of the chair, removed my clothes and put a paper gown on me. Why paper? Think about it and you’ll realize why.

A nurse asked if she would be safe sitting in the room with me. I grunted, “yes,” but my mind was on fire, and after a few minutes I told her:

“I need you to get out of this room and lock the door.”

She did, and I lost it.

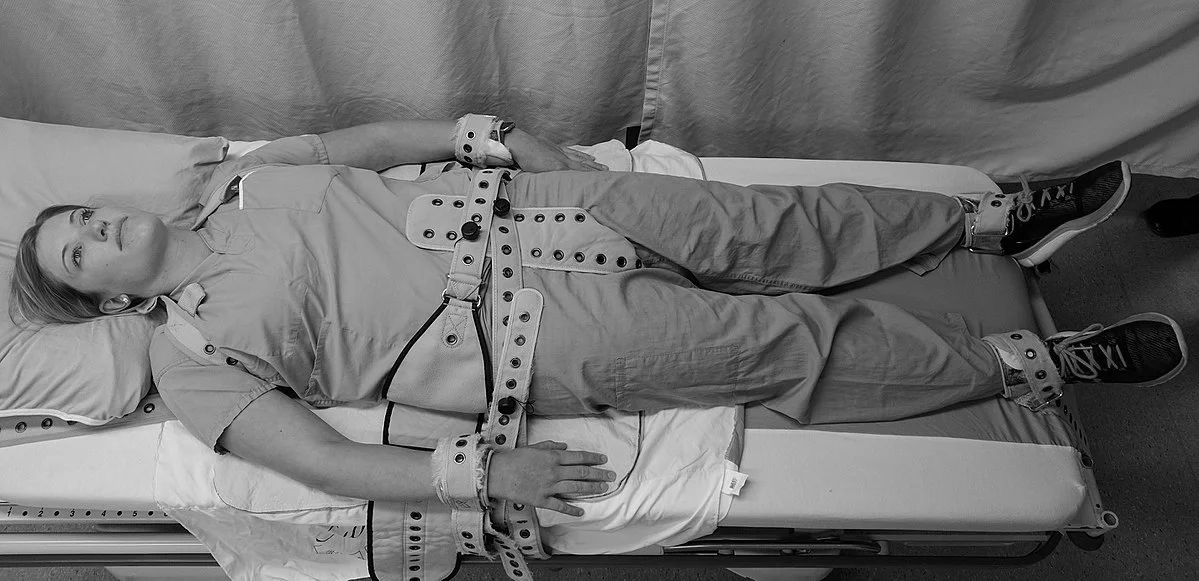

Dramatic recreation

You already know that seclusion rooms are designed to prevent someone from significantly hurting themselves. I knew this too. So I used the room to cause pain that I could control.

I punched the walls. I chained combinations together until my knuckles bled. I screamed. I paced. I raged. When I could no longer lift my hands, I slammed my head against the wall.

I did not feel agony. I WAS agony.

I unleashed all of my panicked energy while the nurses and doctors pleaded for me to stop. Protocol dictated that they stay outside the room. Sure, it would have been nice to have someone restrain me, but the safer course is to let a person burn themselves out until they are no longer a threat to themselves or their caretakers.

Most hospital protocols specify that restraints be used for the least amount of time necessary.

Eventually, everything slowed down. I collapsed onto the mattress and the door opened up. Several large men secured my limbs and put me on a gurney, to which my wrists and ankles were strapped.

Didn’t I write no restraints earlier? They are used as a final resort to protect a person who has clearly demonstrated the recent capacity to hurt themselves, and to protect those around them.

A nurse injected me with Haldol, an antipsychotic drug that “decreases excitement of the brain.” It’s the human equivalent of horse tranquilizer - you get real chill, real quick. Then she gave me another injection to counteract the side effects of Haldol.

I woke up two days later with a pounding headache and swollen knuckles, and all I could think of was how wrong I was so many years ago.

Life on the 7th Shelf is my way of sharing how a person can live well with depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation.

The 7th Shelf was written by Dante in The Inferno, as the Wood of the Suicides.

For me, living on the 7th shelf is challenging but I have found my means for winning the daily battle against the worst my mind can throw at me.

We aim to create a space of hope, filled with resources, information, tools, and more for mental health awareness and suicide prevention. We’re committed to Gordon’s vision of sharing different methods of thinking to help those with and without mental illness live more fulfilling lives.

Contact us

corsetti007@me.com

Call or text 988 for the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline for help. In an emergency, please call 911.

If you or someone you know is seeking help for mental health concerns, visit the National Alliance on Mental Health (NAMI) website, or call 1-800-950-NAMI(6264).

For confidential treatment referrals, visit the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) website, or call the National Helpline at 1-800-662-HELP(4357).