Impulse Control

/“As for impulsiveness, a volume could be written about the disastrous consequences of this symptom. It has ruined many a business, many a marriage, and many a life.”

- Karl Menninger

Before I turned twenty-five I had:

Committed early to college to play lacrosse

Blew all of my money skydiving

Changed my major multiple times

Enlisted in the Marine Corps

Moved into an apartment without steady income

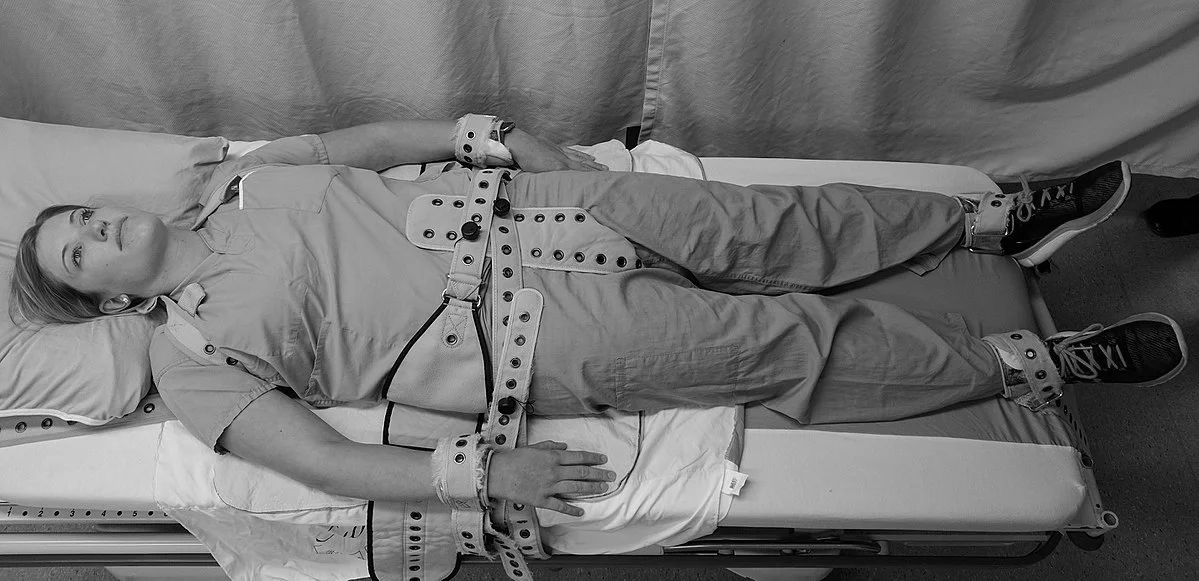

Attempted suicide three times

I was impulsive, and I was young. My prefrontal cortex was still developing.

In fact, some research indicates that, “the frontal lobes, home to key components of the neural circuitry underlying ‘executive functions’ such as planning, working memory, and impulse control, are among the last areas of the brain to mature; they may not be fully developed until halfway through the third decade of life” (Johnson, Blum, & Giedd).

Kids, I get to call them that now that I’m thirty, do not have the mental hardware to deeply consider anything beyond their immediate future.

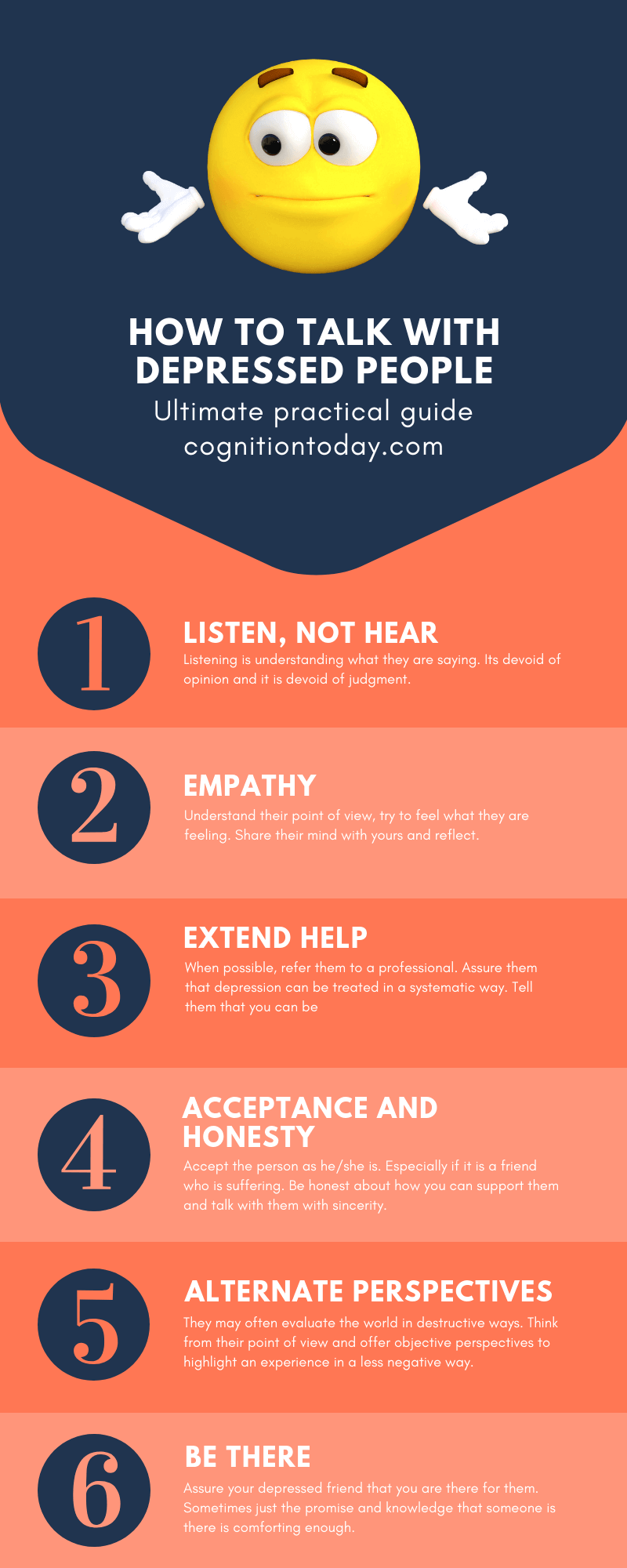

Many adults look at the behavior of adolescents with bemused concern. Surprised at what we consider silly behavior, we ask: “don’t they think about the consequences?” They do! Just not like adults with fully developed frontal lobes.

Kids, for the most part, have a dial-up connection to their impulse control center. Adults have a 4G connection. It is no wonder that young people will think through a decision, experience slow loading times, and decide to do what they want.

The lack of impulse control may be why we see that, “suicide is the 2nd leading cause of death in the world for those aged 15-24 years.”

15-24. Ages where a young person goes through at least three different learning environments, experiences vast changes to their bodies, simultaneously juggles youth and adult personas, and, as if to add more to their plate, every adult asks what they plan to do with the rest of their life.

Add in the potential for bullying, social isolation, poverty, physical and sexual abuse, mediocre parenting, poor parenting, or no parenting, and you can see that kids, despite our adult objections to the contrary, do not have it easy. To say otherwise demeans them, and calls into question the validity of our own growing pains.

Are you worried about your child, but do not know where to start? The American Foundation for Suicide Prevention has an excellent list of resources that will help: https://afsp.org/campaigns/talk-about-mental-health-awareness-month/teens-and-suicide-what-parents-should-know/